What is the most overlooked resource on the planet?

It’s not fossil fuels. It’s not rare metals.

It’s those underappreciated resources we have, the exact materials we casually discard every single day.

Everything that usually ends up in landfills, from food scraps, crop residues, spent grain from breweries to waste cooking oil, etc is actually a reservoir of valuable compounds. These streams can be transformed into bioplastics, renewable fuels, biogas, specialty chemicals, and a whole portfolio of sustainable materials. What we’ve been calling “waste” is, in reality, a feedstock that science and industry are only now beginning to fully utilize.

This is the core idea behind the circular bioeconomy i.e. recognizing that discarded biomass isn’t an endpoint but the starting point of another production cycle. It’s a reminder that we’ve been overlooking one of the most abundant raw materials on Earth.

And while it may sound almost too optimistic, this is where biotechnology and market demand intersect and the innovations emerging from that intersection are genuinely transformative.

Almost around 30% of the world’s food supply is lost or wasted each year, and most of that material ends up decomposing in landfills. As it breaks down, it releases methane (an extremely potent greenhouse gas with 86 times the short-term climate impact of carbon dioxide). In other words, we’re investing resources to grow food, paying again to dispose of it, and then dealing with the environmental fallout it creates. Meanwhile, industries continue spending billions extracting fossil fuels to manufacture plastics and chemicals that could have been made from those very waste streams.

From an economic standpoint, the logic simply doesn’t hold.

This is where the circular bioeconomy reshapes the narrative. In this system, waste isn’t an endpoint, it becomes a feedstock that loops back into production. The science behind this shift is compelling. Fermentation technologies can convert all the food waste into organic acids, alcohols, and intermediates that is further used to produce bioplastics, renewable fuels, and specialty chemicals.

Microorganisms readily metabolize these waste substrates to create polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs), the biodegradable polymers gaining global attention. Crop residues such as rice straw and wheat straw can be hydrolyzed into fermentable sugars for low-carbon fuels or bio-based materials. Waste cooking oils, once treated as a disposal problem, are being upgraded into sustainable aviation fuel in facilities like OMV’s Schwechat plant. Even brewery spent grain which previously cost European producers €75–100 per ton to get rid of has become a valuable input for next-generation bioplastic production.

Once you look at the data, the magnitude of the circular bioeconomy becomes impossible to ignore.

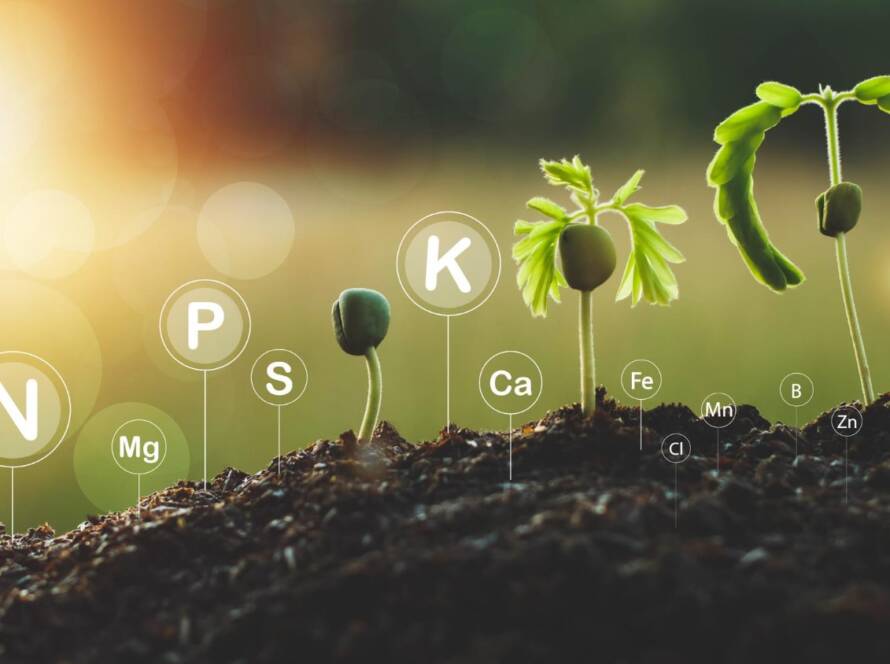

Take a modest urban stream of 100 tons of food waste generated per day. Run it through an anaerobic digestion, that same volume produces enough renewable energy each year to supply roughly 800–1,400 households. And the process doesn’t just ends with biogas, all the leftover digestate functions as a nutrient-rich biofertilizer, helping close nutrient loops and cutting reliance on synthetic fertilizers. Several European biorefinery projects already operate on this model, converting municipal organic waste into high-value materials, including PHAs and other bioplastics.

Governments are starting to quantify the upside as well. Estimates straight from France suggest that large-scale conversion of kitchen waste into biogas and biopolymers could save around $167 billion annually while diverting 88 million tons of food waste from landfills each year. Industrial studies reinforce this feasibility, engineered microbial systems have achieved production titers of 82 g/L of commercially valuable chemicals using waste-derived substrates that too without antibiotics or external inducers demonstrating that these processes scale effectively.

Agricultural residues present a similarly vast resource base. Materials like rice straw, often burned in fields and responsible for significant seasonal air pollution, are actually rich in cellulose and lignin. These components can be separated into fermentable sugars and then transformed into microbial oils, low-carbon fuels, or biodegradable polymers, all compatible with existing refinery pathways.

Okay, let’s acknowledge the challenges as well.

The circular bioeconomy isn’t a turnkey system, at least not yet.

Waste-derived feedstocks vary widely, and that variability has real consequences. For instance, used cooking oil collected from different regions can contain very different salt concentrations, which accelerates corrosion in processing equipment. Facilities have to be designed to handle those fluctuations in quality.

On the lignocellulosic side, breaking agricultural residues into fermentable sugars is still one of the biggest technical bottlenecks. Enzymes remain expensive, reaction rates are slow, and large-scale pretreatment systems require significant capital.

Beyond the biochemical hurdles, the physical infrastructure simply isn’t there in most places. Collecting, sorting, transporting, and preprocessing heterogeneous waste streams demands systems that many cities and rural areas have not yet built. Coordinating government departments, municipal waste agencies, industries, and consumers adds an extra layer of complexity that few regions have fully untangled.

Yet despite these constraints, integrated circular bioeconomy pilots across Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia are already converting agricultural and food residues into entirely new value chains, banana and pineapple waste becoming textile fibers, fish by-products being turned into feed ingredients and biofuels, and agro-waste streams supplying biogas and biopolymers. Technology costs are falling, microbial processes are improving, and policy frameworks are finally beginning to align with the needs of large-scale biorefinery development.

Ultimately, the idea is simple. Materials are considered as “waste” only when we fail to get some value out of it. With the right technologies, policies, and infrastructure, those discarded resources turn into feedstocks that generate energy, materials, income, and climate benefits all at once.