What may turn out to be the most consequential change in farming since the Green Revolution isn’t coming from hardware or data analytics. It’s coming from a quiet but accelerating shift in inputs. Agriculture is steadily moving away from heavy dependence on synthetic chemicals and toward biological products designed to work with natural systems rather than override them.

This change has moved well beyond pilot trials and niche adoption. Biostimulants that were once used cautiously on small acreage are now part of a global market worth billions, growing steadily year after year. Biofertilizers are following the same trajectory, shifting from occasional supplements to routine tools in nutrient programs across diverse crops and geographies. Practices that were once labeled unconventional are steadily becoming part of everyday farm management.

This isn’t a trend driven by ideology. It’s being pushed forward by economics, regulation, soil degradation, and the limits of chemical-only approaches. The bio-based transition is already underway, and its momentum suggests it will redefine how food is produced far more deeply than most technologies grabbing headlines today.

The shift toward biological inputs isn’t happening by choice alone infact it’s being forced by a system that’s running out of room to maneuver. Decades of fertilizer-heavy farming have left a deep mark. Roughly one-fifth of the world’s cropland has seen its productive potential decline, and soil degradation has become widespread, with large portions of agricultural land now struggling to function as healthy ecosystems. At the same time, synthetic fertilizers remain a major source of greenhouse gas emissions and water pollution, generating environmental costs that ripple far beyond the farm gate.

The yield gains of the Green Revolution came with hidden liabilities. Intensive input use boosted production in the short term, but it also stripped soils of biological resilience, reduced biodiversity, and locked farmers into systems that demand ever-higher chemical inputs just to hold yields steady. Instead of progress compounding, dependency compounds. The result is a production model that feels less like advancement and more like running faster to stay in place.

What’s changed is awareness beyond the field. Consumers are paying attention to how food is grown, not just how much is produced. Willingness to pay for cleaner, higher-quality food is rising across major markets, and organic production continues to expand rapidly. That shift in demand is sending a clear signal upstream i.e. farming systems built entirely on synthetic inputs are losing social and economic acceptance, and food production is being pushed by markets as much as by policy toward more biologically grounded approaches.

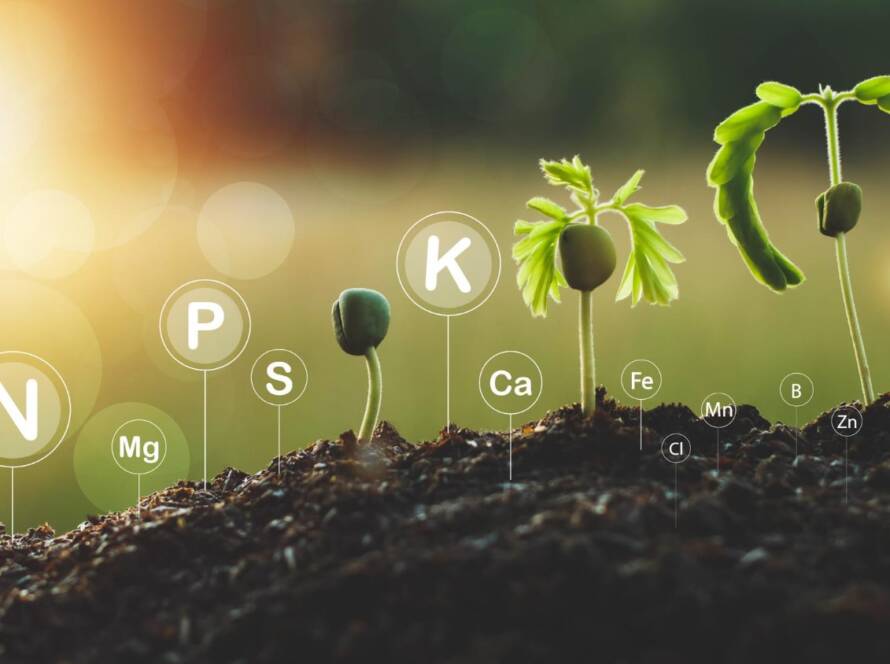

Biological inputs are gaining ground because their advantage lies in range, not just performance. Bio-based inputs tackle several pressure points at once instead of shifting problems downstream. They reduce reliance on fossil-derived fertilizers, rebuild soil function rather than stripping it, help crops cope with climate stress, and lower the environmental cost of food production all while aligning with what consumers increasingly expect from modern agriculture.

Field research supports this shift. Biostimulants consistently improve fertilizer use efficiency, allowing farmers to achieve the same or better results with significantly lower input rates. Microbial biofertilizers enhance nutrient availability by activating soil biology, improving aggregation, and increasing water-holding capacity that too without leaving behind harmful residues. Trials show that crops treated with microbial stimulants absorb nutrients more effectively and develop stronger tolerance to drought, salinity, and temperature stress.

Government action is now aligning with market demand. In Europe, agricultural policy is actively steering farmers away from heavy chemical dependence by encouraging the use of biological inputs under the Farm to Fork strategy. India has taken a large-scale approach through its National Mission on Natural Farming, expanding access to bio-inputs by setting up localized production hubs that reach millions of growers. In the United States, updated regulations including the Plant Biostimulant Act have simplified approval processes, allowing biological products to move more quickly from development into widespread farm use.

Taken together, biology-based inputs are no longer experimental tools instead they are becoming structural components of how agriculture adapts to economic, environmental, and societal realities.

This shift isn’t speculative anymore, it’s visible in adoption patterns. Biostimulants have already moved beyond early adoption. Most farmers worldwide now incorporate them to strengthen crop tolerance and maintain consistent yields. Usage remains highest in North America and Europe, where regulatory clarity and on-farm familiarity have driven widespread uptake. At the same time, the Asia-Pacific region is emerging as the fastest-growing market, fueled by increasing demand for organic food and large-scale government initiatives across India, China, and Southeast Asian nations that are accelerating adoption.

Capital flows reinforce the trend. A growing share of agricultural research funding is now focused on biological and nature-based solutions rather than purely synthetic chemistry. Large multinational agribusiness firms have responded by building dedicated bio-based portfolios, signaling long-term commitment rather than short-term experimentation. Capacity expansions over the past year alone reflect confidence that demand is structural, not temporary. The market is moving, and the industry is moving with it.

Why this transition actually matters is because modern food systems have been built in ways that place heavy pressure on ecosystems and, in many cases, public health. Changing that trajectory requires tools that can be applied broadly without undermining food production. Bio-based inputs fit that requirement. They offer a way to improve sustainability at scale while maintaining, and often enhancing, agricultural performance.

More importantly, they challenge the long-standing assumption that productivity and environmental responsibility are opposing goals. The growing adoption of biological solutions shows that it’s possible to grow more food for a larger population while reducing ecological harm. That balance isn’t theoretical anymore, it’s becoming operational.